To Teach or Not To Teach: Is Shakespeare Still Relevant to Today’s Students?

by Amanda MacGregor Jan 04, 2021 SLJ

Here’s a sentence we couldn’t write without William Shakespeare, who invented or introduced nine of these words:

Ask if Shakespeare’s time-honored works and syllabus fixtures should be bumped to embrace the multitudinous other writers and you get hostile, fretful, quarrelsome, or sanctimonious reactions.

Shakespeare was a genius wordsmith who created engaging works that spoke to the human condition, psychology, and identity. His masterful wordplay, creative use of language, biting wit, puns, and innovative characters and plots have delighted generations of readers and made a lasting impact on literature and the English language. The plays, sonnets, and poems the Bard wrote in his lifetime (1564–1616) are mainstays of the high school English syllabus. But should all that ensure him a spot in the curriculum in perpetuity?

Ben Jonson, Shakespeare’s contemporary and fellow playwright, asserted that Shakespeare was “not of an age but for all time.” But he was very much of his time. Shakespeare’s works are full of problematic, outdated ideas, with plenty of misogyny, racism, homophobia, classism, anti-Semitism, and misogynoir. Which raises the question: Is Shakespeare more valuable or relevant than myriad other authors who have written masterfully about anguish, love, history, comedy, and humanity in the past 400-odd years?

A growing number of educators are asking this about Shakespeare, along with other pillars of the canon, coming to the conclusion that it’s time for Shakespeare to be set aside or deemphasized to make room for modern, diverse, and inclusive voices. But the essential questions go far deeper than simply “to teach or not to teach.” Educators must ask whose stories are valued and what voices are elevated or silenced. What does a syllabus say about your students and their places in the world? Educators grappling with these questions are teaching, critiquing, questioning, and abandoning Shakespeare’s work, and offering alternatives for updating and enhancing curricula.

|

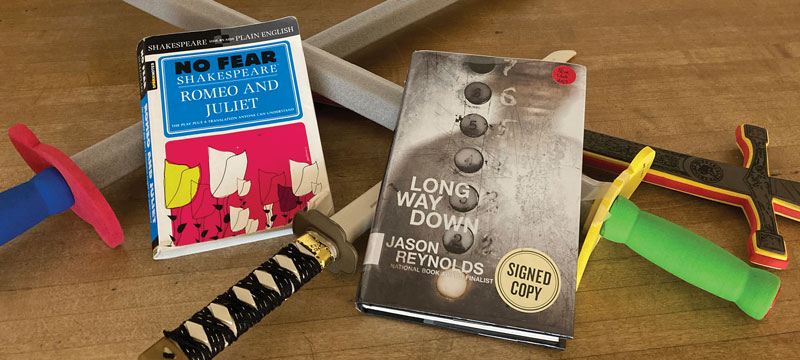

Brittany Greene’s students engage with plastic swordplay and Jason Reynolds’s Long Way Down.Photo courtesy of Brittany Greene |

New takes on old plays

Brittany Greene teaches Romeo and Juliet to ninth graders at Nazareth (PA) Area High School. Recently, her approach to this play has changed. “After reading about a woman named Laura Bates who taught Shakespeare to prison inmates, I was inspired to focus more on the violence within Romeo and Juliet,” she says. Greene pairs the play with Jason Reynolds’s Long Way Down, about a teenager weighing retribution after his brother is shot and killed, and has her students make connections between the main characters in both. Students “analyze the external factors that affect Romeo and Will [from Long Way Down] and discuss the result of those external motivators on the characters’ behavior,” she says.

Sarah Mulhern Gross, a ninth and twelfth grade English teacher at High Technology High School in Lincroft, NJ, also teaches Romeo and Juliet, but “through the lens of adolescent brain development with a side of toxic masculinity analysis,” she says.

Adriana Adame teaches at a charter school focused on college readiness and trauma-informed care in Texas. “All of our kids have higher ACE [adverse childhood experiences] scores, and that is taken into consideration with how and what we teach,” she says. With Hamlet, she focuses on the trauma, along with coping mechanisms and grief. Adame brings specialists in to speak about “what to do with grief and ways to keep from spiraling when faced with stressful situations,” she says.

Elizabeth Neilson, a high school English teacher at Twin Cities Academy, a college prep–focused charter school in St. Paul, MN, uses Coriolanus to teach Marxist theory. “When they read a text written centuries ago [that] addresses events and people from even longer ago, it is easier for them to divorce their analysis from their biases and inherited beliefs about class in the modern era,” Neilson says.

Another approach to Shakespeare is pairing the source material with retellings that offer creative, modern, inclusive twists on the plays. Dahlia Adler, editor of the forthcoming YA anthology That Way Madness Lies: Fifteen of Shakespeare’s Most Notable Works Reimagined (Flatiron, March 2021), believes these new takes on classic stories are “more accessible to a much greater range of readers who don’t often get to see themselves in the books they read for school.”

|

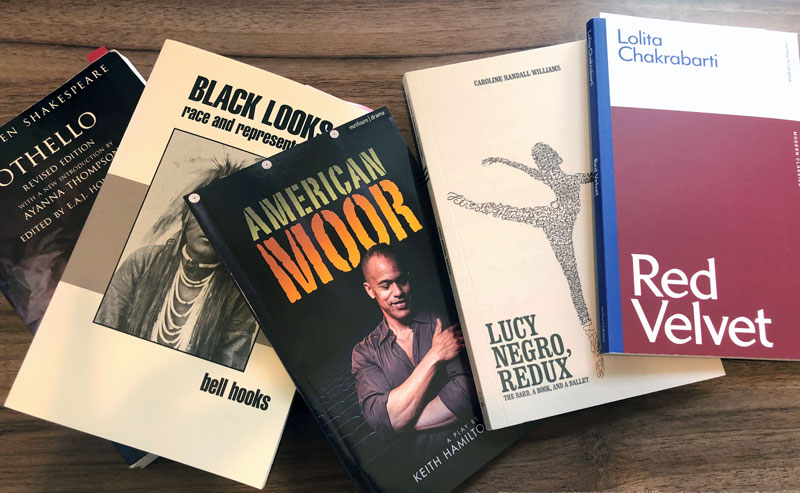

Ayanna Thompson, a scholar of Shakespeare and race, suggests these readings alongside Othello.Photo courtesy of Ayanna Thompson |

Author Lily Anderson’s retelling of As You Like It is included in the anthology, with a plot line involving a summer camp in the woods for adults. One of Anderson’s favorite things about Shakespeare’s works is how reference-heavy they are. “Each play contains a secret reading list of myths, histories, parables, and other plays,” she says. By keeping Shakespeare and his works relevant, “we are also keeping alive a connection to stories going back to antiquity, a chain of popular culture from present to remote past.”

While Shakespeare continues to be widely taught, part of reconsidering the canon must contend with how he became a staple. Shakespeare can show up year after year on a syllabus because teachers may have little autonomy to choose their curriculum, using texts their schools own, and have little to no budget to change them.

Ayanna Thompson, director of the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies and professor of English at Arizona State University, is a Shakespeare scholar with deep roots in African American and postcolonial literature. On why the playwright’s works have become fixtures in education, Thompson says, “Shakespeare was a tool used to ‘civilize’ Black and brown people in England’s empire. As part of the colonizing efforts of the British in imperial India, the first English literature curricula were constructed, and Shakespeare’s plays were central to that new curricula.”

The meaning of “universal”

If the Bard became a fixture in part due to colonialism, another assumption to consider is what it means when people say his works, or any, are “universal.”

“We need to challenge the whiteness of [that ] statement: The idea that the dominant values are or should be ‘universal’ is harmful,” says Jeffrey Austin, ELA department chair at Skyline High School in Ann Arbor, MI. If teachers want to teach themes traditionally covered in canonical works, they can also look to modern voices that speak to those themes through a wide range of perspectives beyond the dominant identities and values.

Another common concern is that if students don’t study Shakespeare, they will be at an academic disadvantage. But Thompson questions this line of thought. “At a disadvantage for what? The premise of this question seems to be framed on an older colonial/imperial model. A true disadvantage is not knowing how to read, understand, analyze, and grapple with the cultural or political contexts of any piece of literature,” she says.

|

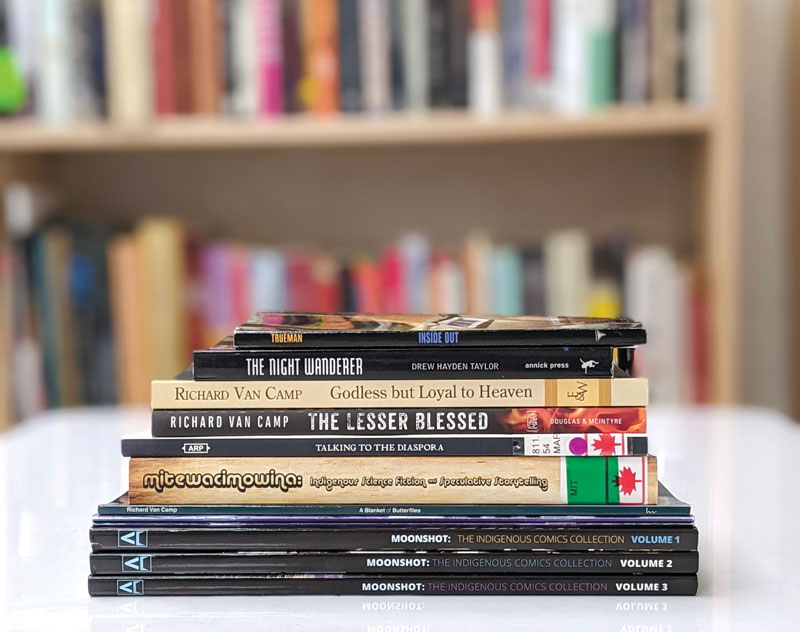

English teacher Cameron Campos teaches works by mostly Canadian/North American Indigenous authors instead of those by Shakespeare and other canonical writers.Photo courtesy of Cameron Campos |

Claire Bruncke, who, until this year, taught language arts classes at a small, rural public school in Washington State, dropped Shakespeare from her syllabus. “I asked my principal if there was a requirement for how much [Shakespeare] I needed to cover,” she says. She was told that as long as she was teaching the standards, it didn’t matter. She used the time they would have spent on Shakespeare for writing labs and reading anthologies and novels not typically found in the canon. “My students’ [positive] response to this work solidified my decision,” Bruncke says.

Cameron Campos, an English teacher at Foothills Composite High School in Alberta, Canada, has generally moved away from teaching what’s considered classic. “My grade 11 and 12 courses use texts almost entirely written by Indigenous authors, except for a few Canadian classic short stories and some works by contemporary poets,” Campos says. “The only author that the curriculum dictates we teach is Shakespeare.” However, with this year’s provincial exam likely to be canceled or made optional, Campos was able to skip Shakespeare and teach The Thanksgiving Play by Larissa FastHorse instead.

Liz Matthews, a ninth grade English teacher at Hartford (CT) Public High School, a school that is 95 percent Black and Latinx, has also chosen to pass on Shakespeare.

“I replaced Romeo and Juliet with The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros last year and Long Way Down by Jason Reynolds this year,” she says. “Simply put, the authors and characters of the two new[er] books look and sound like my students, and they can make realistic connections. Representation matters.”

Defenders of the Bard

A quick glance at the Internet shows that many are infuriated by the question of removing or replacing Shakespeare in schools. But if education values innovation, then curriculum revisions should not be controversial, proponents insist. If the point of language arts classes is to explore literature through critical analysis; grow writers; increase skills, literacy, and meaningful engagement; and create lifelong readers, students can do that through any text.

“All pedagogy needs to evolve to reflect different modes of learning, and in turn, syllabi should never be written in stone,” says Thompson, who doesn’t believe a syllabus needs to be changed in a binary way by replacing Shakespeare with other authors. Thompson offers some suggestions for authors to add in order to enrich study of Shakespeare. “Toni Morrison, August Wilson, Amiri Baraka, Djanet Sears, Gayl Jones, W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, and countless modern artists from Africa, the Caribbean, and Asia have written in response to Shakespeare,” Thompson says. “There are rich global perspectives from which Shakespeare can be approached, taught, and analyzed.”

Lorena Germán, an Austin, TX, educator and a cofounder of DisruptTexts, suggested alternatives in a #DisruptTexts Twitter chat. “Trust me, your kids will be fine if they don’t read [Shakespeare],” Germán wrote. She suggested educators update their syllabus to include Dutchman by Amiri Baraka, Color Struck by Zora Neale Hurston, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf by Ntozake Shange, and Athol Fugard’s “Master Harold”… and the Boys. “These are all plays and have so much to break down. They’re deep and powerful.”

“There is nothing to be gained from Shakespeare that couldn’t be gotten from exploring the works of other authors,” Austin says. “It’s worth pushing back against the idea that somehow Shakespeare stands alone as a solitary genius when every culture has transcendent writers that don’t get included in our curriculum or classroom libraries.”

Campos agrees. “Surely no author should be given such an elevated place in our curriculum,” he says. “Asking ourselves why we privilege certain texts and authors is a conversation more teachers need to be having.”

Let the past be prologue

Bruncke, who focuses on student choice, has never had a student ask why she stopped teaching Shakespeare. “I know we must do better in the ELA classroom to stray from centering the narrative of white, cisgender, heterosexual men, and eliminating Shakespeare was a step I could easily take to work toward that. And it proved worthwhile for my students.”

Intentional or not, the reliance on older works also sends the message to students that modern literature isn’t as worthy. Are we making room for the canon to evolve and change, to bring in current and future classics?

“I frequently see teachers singing the praises of a book like Dear Martin by Nic Stone, but in the same breath, telling students to read it on their own time, as if it doesn’t deserve classroom space,” says Austin. “In my conferences with students across districts, they report the same frustrations: The books they want to read are pushed to the side as unserious entertainment, while books they don’t want to read become the centerpieces of their learning.”

Austin goes on to talk about the many BIPOC teachers and scholars who have long been challenging the very idea of the canon and pushing for more inclusive classrooms. “We’ve been given the tools, strategies, and frameworks, but no one can give us the belief, commitment, and wherewithal. That’s on us,” he says. “It’s hard work, because we’re challenging deeply ingrained beliefs around what and whose knowledge is essential. Making our spaces more identity-affirming and equity-driven requires constant effort.”

Reconsidering the canon can also drive home the point that literature belongs to us all. With new additions, richer conversations may emerge, and there may be deeper personal engagement with texts, more connections, and more passion. Educators must also contend with their own nostalgic attachments to and beliefs in the established works. Embracing the diversity in literature will affirm students’ lives, voices, and experiences, a growing number of educators say: Let what’s past be prologue as we look ahead to the future of teaching literature.

Check out the next blog- 10 Works Reimagined for YA Readers. Current YA authors reimagine the stories of the Bard in these 10 titles.

Comments

Post a Comment